The "Right" Way to Be Wrong: A Leader's Guide to Implementing Change

Discover how successful leaders navigate organizational change and transform resistance into innovation – practical insights from industry experts.

Welcome to another episode of Tech Trendsetters, where we explore the intersection of technology, business transformation, and human behavior. In one of the previous episodes, we touched on the topic of transforming decision-making in organizations. Today, we're pulling back the curtain to examine something even more fundamental: a self-reinforcing pattern called “The Disablement Cycle.”

Here’s what makes this topic particularly fascinating: unlike many organizational problems that stem from clear mistakes or bad decisions, the Disablement Cycle emerges when everyone is actually doing their job correctly. Yes, you heard that right – sometimes doing the "right" thing is exactly what's wrong.

Too many times in my life, I've heard the phrase: “We have brilliant people, cutting-edge technology, and unlimited resources. So why does it take us six months to implement a simple feature that our smaller competitors ship in weeks?”

This experience reminded me of a quote from Charles de Gaulle:

History does not teach fatalism. There are moments when the will of a handful of free men breaks through determinism and opens up new roads.

Today's episode is about finding those moments and seizing them – about breaking through the determinism of established processes to open up new roads for your organization. What you will know:

Why smart teams often resist smart changes;

The hidden psychology behind organizational inertia;

Practical, proven strategies for implementing change without creating chaos;

And most importantly, how to turn the vicious cycle of disablement into a virtuous cycle of enablement;

Whether you're a tech leader struggling with bureaucracy, an engineer frustrated by approval processes, or a manager trying to find a balance of control, this episode will give you practical insights to break free from the cycle of organizational paralysis.

Understanding the Disablement Cycle

Let's see what is the concept of the Disablement Cycle. It's a pattern commonly found in environments with a lot of approval processes, where getting anything done takes a lot of effort and costs more money. This, in turn, leads to projects becoming more expensive. The natural reaction to more money being at stake is to add more controls. However, doing so adds even more friction, feeding the disablement cycle. Organizations subjected to this cycle are often referred to as those "where it's impossible to get anything done."

Now, here's the interesting part: each involved party in this cycle is doing the right and logical thing within their context. If a project asks for a lot of money, it's logical to add additional checks and controls to reduce the risk to the organization. After all, who would want to approve a million-dollar project without any oversight?

On the other hand, if the overhead for projects due to friction is high, it's more efficient to make bigger projects. If all approvals, reviews, and the associated preparation for a project amount to $100,000, it makes little sense to start a $100,000 project because the "tax" due to process friction would be 100% on top of the project cost. If you bundle all your ideas into a single project for $1 million, you only pay a 10% "tax." So, it's the right thing to do – you are actually saving the company money (at least, that's what you tell yourself to sleep at night).

This is where the Disablement Cycle becomes self-reinforcing. Each party is doing the right thing within their scope of work, making it difficult to break the cycle by simply telling people they are doing it wrong. Generally, it’s not a good idea to tell people they’re wrong, but.. They aren't doing anything wrong within their context.

Real-world examples of the Disablement Cycle can be found in many large tech companies. For instance, a software engineer might have a great idea for a new feature that could significantly improve the user experience. However, to get the project approved, they need to go through multiple layers of management, each requiring detailed project proposals, cost estimates, and risk assessments. By the time the project is finally approved, the market has already shifted, and the feature is no longer as relevant.

Breaking this cycle is not easy, but two factors can help: external pressure and establishing a broader end-to-end view and set of responsibilities. When external pressure builds up, it can help people question existing ways of working, but it may already be too late by then. On the other hand, when people see and are rewarded for end-to-end results, they will stop optimizing for their local portion of the cycle and start optimizing for overall success.

The Anatomy of Resistance

Now that we understand the Disablement Cycle, let's explore why it persists. Why do organizations resist change even when it's clear that the current system is not working? The answer lies in the anatomy of resistance.

First, we need to revisit Larman's Laws of Organizational Behavior. These laws, based on decades of observation and organizational consulting, provide insight into why changes are so difficult.

Law #1 states that organizations are implicitly optimized to avoid changing the status quo in power structures. In other words, the very people who have the power to change things are often the ones most invested in keeping things the same – such is the paradox.

The role of middle management and specialists in resisting change cannot be overstated. These individuals often have the most to lose when change occurs, as it can disrupt their power structures and job security. As Larman's Law #2 states, any change initiative will be reduced to redefining or overloading the new terminology to mean basically the same as status quo. So, your "agile transformation" might end up being just a fancy way of saying "business as usual."

Cultural and systemic factors also contribute to resistance. As Howard Schwartz and Stanley M. Davis argue, strategies must align with organizational culture. If your company has a culture of risk aversion and bureaucracy, trying to implement a fast-paced, agile approach is going to be an uphill battle – no matter how hard you push, it's just not going to work.

TLDR here: If you truly want to change culture, you must begin by changing the structure, as culture rarely changes on its own. This is why deep frameworks of thought, like organizational learning, often struggle to gain traction or make a significant impact on their own. In contrast, systems like Scrum, which prioritize structural change from the outset, tend to influence culture more rapidly and effectively.

The Psychology Behind Resistance

The psychology behind resistance is also worth examining. As Paul Strebel highlights, there are often differing perceptions of change between managers and employees. Managers may see change as an opportunity for growth and innovation, while employees may see it as a threat to their job security and way of working. It's like trying to convince a cat to take a bath – they might go along with it, but they're not going to be happy about it. This disconnect can lead to resistance and lack of buy-in from employees.

A real-life example of this resistance can be seen in Nick Tune's experience with a senior developer. I've heard plenty of similar stories. The situation can be briefly described as follows: in an old team, there is a certain senior developer who has been holding the codebase together for many years. A new specialist comes in with new processes and a new architecture. The old specialist begins to sabotage the changes, leading to a split in the team.

Apparently, the senior developer expected recognition from management for his long-term contribution. Instead, he received a demonstration of distrust in the form of delegating authority to an externally hired specialist who could solve the problem (unlike him) and to whom he now had to report. His psychological defense was quite predictable in this scenario ¯\_(ツ)_/¯.

The catalyst for the conflict was the difference in knowledge levels. As Nick Tune, was on one side of the conflict, it suggests that the senior developer may have had less expertise in certain areas.

Leveling the knowledge gap is the main way to eliminate the causes of resistance.

Real Reasons for Resistance

However, the knowledge gap itself was not the cause of the conflict, but merely the breeding ground. The real cause was forcing changes on the team without sufficient information and awareness.

How could this situation have been prevented? One option is to simply avoid forcing change without sufficient team awareness. Kent Beck had already warned about the delicacy of implementing pair programming. This would have prevented the split but not eliminated the resistance.

The resistance had two main causes:

undervaluation of the long-term employee;

and his sense of inferiority in the face of the new employee's knowledge.

The first could be solved by assigning the undervalued employee the most responsible task of implementing changes, allowing him to maintain his position and feel trusted. The second could be addressed by making knowledge a point of prestige, and constantly leveling the knowledge gap (however this depends on individual learning abilities).

Political Aspect

Ultimately, there was also a political aspect – a struggle for influence over the team. Nick Tune chose too broad a front for change, where he couldn't ensure the superiority of the forces of change over the forces of resistance. He eventually realized this and increased the specific strength of the changes by reducing the team size, weakening the resistance. However, this forced him to fire the main centers of resistance (who might still have been good specialists after all).

Implementing changes incrementally might have allowed Nick to form a support base within the team, changing the balance of power. Faced with the risk of remaining an outcast, the senior developer might have refrained from sabotage attempts.

Last but not least, bringing the conflict into the public sphere was perhaps reckless, as people unite against common threats, potentially reducing Nick's support base even more.

Reasons for Resistance to Change

Overall, there are four reasons for resistance to change that are commonly discussed in change management literature. These insights, shared by various experts in the field, help us understand why people often push back against transformation. By addressing these points, organizations can implement their own successful changes.

First, resistance arises because the rewards for making changes are often delayed, while the effort and inconvenience are immediate. People may feel reluctant to invest time and energy when the payoff feels distant. People need to know why to climb a mountain, knowing what's on the other side and why is it worth the efforts.

Second, change disrupts established routines and familiar ways of working. This disruption can create discomfort and inconvenience, which naturally leads to resistance. If you rearrange the furniture in your flat – sure, it might look better, but now you keep bumping into things because you're not used to the new layout.

Third, when changes are introduced as recommendations rather than mandatory standards, people may not take them seriously. Without clear accountability, the adoption of new behaviors or processes tends to be slow or inconsistent.

Finally, a common mental barrier is the belief that external processes, methods, or support cannot truly improve the situation. This skepticism often leads to resistance against adopting external tools or advice or hiring consultancy services. It's like going (or not going at all) to a therapist and saying, "What do they know about my life? They can't possibly help me.”

Successful Change Management on a Tactical level

Now that we understand the anatomy of resistance, let's jump into the practical aspects of implementing changes in a team on a tactical level. As we've seen, resistance to change is a common challenge, but there are strategies and techniques that can help overcome it.

A Quick Summary for Busy Readers

If you’re in a rush but want actionable insights, you can explore resistance to change and learn strategies from experts such as:

Michael Armstrong, with main causes that help understand employees’ struggles during transitions;

James O'Toole, who offers 33 hypotheses about the reasons behind resistance.

Edgar Schein, who suggests paying attention to cultural factors during strategic changes.

John Kotter, who proposes unconventional methods to persuade employees of the necessity of change.

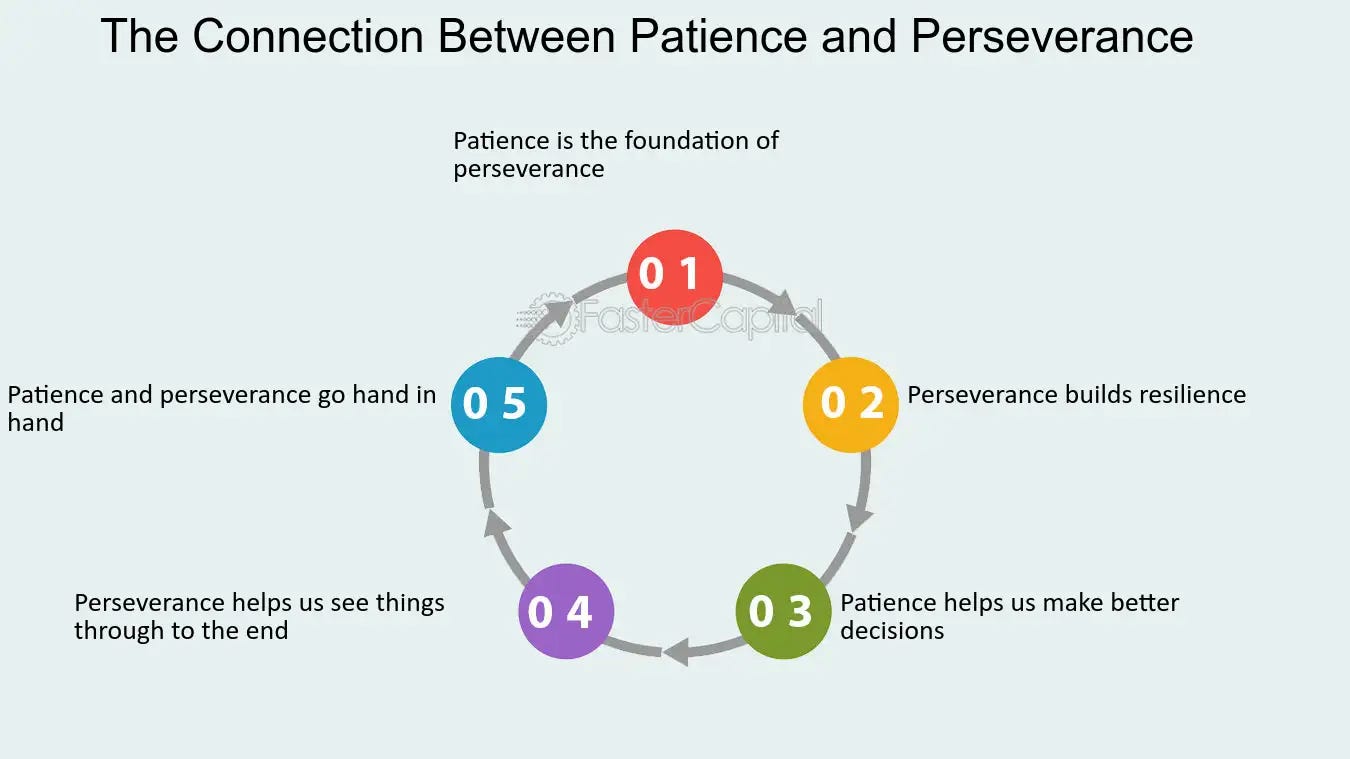

Patience and Perseverance

First and foremost, it's important to recognize that implementing changes is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Every team is different, and what works for one may not work for another. However, there are some general principles that can guide the process. As we’ve already identified, there are four key reasons for resistance to change, and understanding these reasons can help tailor your approach to your specific team.

One of the most important things to keep in mind is the need for patience and persistence. As the saying goes, "Rome wasn't built in a day," and neither are successful change initiatives. It takes time for people to adapt to new ways of working, and it's important to give them the space and support they need to do so. Trying to force change too quickly can backfire and lead to even greater resistance.

Targeted Solutions and Incremental Changes

From my personal experience, I know of only one effective way to bring about change, and that is to identify problems and, in response to specific problems, offer specific solutions. This targeted approach ensures that changes are relevant, actionable, and more likely to be accepted by the team.

Avoid proposing wholesale adoption of new approaches, like DDD or Agile, as this can create uncertainty and additional burdens for the team. Instead, identify the most pressing issues and introduce relevant solutions gradually.

For example, if a particular DDD tactical pattern solves a problem, there's no need to insist on a full transition to DDD. Similarly, if "Program Management" addresses a specific challenge, don't push for a complete shift to SAFe or DAD. By focusing on incremental improvements, you can reduce resistance and increase the likelihood of successful adoption.

Engaging the Team and Fostering Understanding

Engaging the team in the change process is essential for success. As Henry Ford once said:

Quality means doing it right when no one is looking

To achieve this level of commitment, it's crucial to foster a unified understanding and complete awareness among the team members.

Take the time to explain the reasoning behind the changes and illuminate the connections between cause and effect. By facilitating bottom-up, self-organizing change rather than imposing top-down directives, you can create a sense of ownership and buy-in among the team. This approach helps to minimize resistance and ensures that changes are more likely to stick.

Remember, implementing changes in a team or whole organisation is a challenging but rewarding process.

Successful Change Management on a Strategic Level

Alright, it's time to roll up our sleeves and get even more practical. We've talked a lot about the why of resistance and even covered some basic tactical guidelines; now let's talk about the how of overcoming it on a more strategic level.

Here’s the thing to always keep in mind: resistance to change is a natural organizational response. It’s not some evil force trying to sabotage your brilliant ideas. It’s a reflection of the complex play between leadership actions, organizational patterns, employee behavior, and collaborative efforts. And as much as we might want to, we can’t just snap our fingers and make it disappear.

The good news are: while resistance is inevitable, it’s also manageable. In fact, when approached strategically, resistance can actually become a catalyst for innovation and growth.

Leadership Sets the Tone for Change

Let’s start with the obvious: leadership. If resistance to change is a fire, leadership is either the water that extinguishes it – or the gasoline that makes it spread.

Strategic change begins at the top. Leaders aren’t just decision-makers; they’re storytellers. They provide the narrative that helps employees understand why the change is happening, where the organization is headed, and how everyone fits into the picture. Without this narrative, resistance thrives in the vacuum of uncertainty.

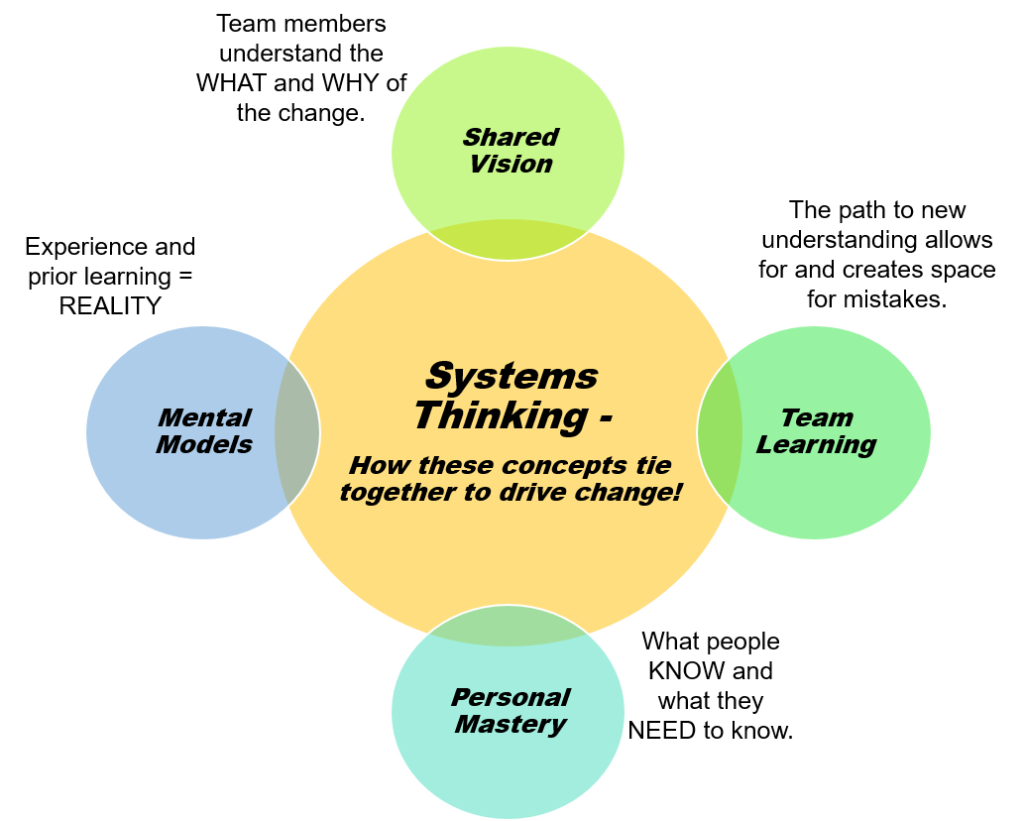

As Peter Senge emphasizes (a founder of Society for Organizational Learning), leaders must align their experience and actions with the challenges their organization faces. But Senge takes it a step further: in a learning organization, leaders aren’t just managers of change; they are designers, stewards, and teachers. Their role is to create the conditions where people can expand their capabilities, work productively toward shared goals, and learn continuously.

For example, rushing into initiatives with “fast food” solutions – like a one-day workshop to overhaul a company – might seem efficient but often backfires. Uncertainty in leadership creates hesitation and mistrust, fueling more resistance.

Practical Steps for Leaders

Communicate the Vision Clearly and Consistently;

Resistance often stems from confusion or uncertainty. Leaders must articulate a clear and compelling vision for the future, explaining not just what is changing, but why it matters. This narrative should be reinforced through every communication channel, from town halls to one-on-one conversations.Model the Change You Want to See;

Actions speak louder than words. If leaders want employees to embrace collaboration, agility, or innovation, they must embody these behaviors themselves. As the saying goes, “Leadership is caught, not taught.”Build Trust Through Early Wins;

Small, visible successes can help reduce skepticism and build momentum. Identify quick wins that demonstrate the benefits of change, and celebrate these achievements publicly.

The Leadership Paradox

Here’s another paradox of leadership in times of a change: while leaders must guide and inspire, they must also let go of control. The best leaders decentralize their authority, empowering employees to take ownership of the change process. This doesn’t mean abdicating responsibility – it means creating the conditions where everyone in the organization can contribute to success.

Aligning Culture with Strategy

Here’s another hard truth: culture eats strategy for breakfast. You can have the most innovative plan in the world, but if your organizational culture doesn’t align with it, good luck with that. Culture is the invisible operating system of your organization, dictating how people behave, make decisions, and respond to change. If that system is incompatible with your strategy, resistance will flourish like weeds in a neglected garden.

Why Culture Matters

As Peter Senge reminds us, organizations are not static entities – they are living systems. And in these systems, culture is the glue that holds everything together. It shapes the mental models employees use to interpret change, their willingness to collaborate, and their capacity to learn. Resistance often arises when there’s a disconnect between the existing culture and the demands of the change initiative.

Take Netflix as an example. When Netflix made the pivot from DVD rentals to streaming, it didn't just slap a new business model onto its existing structure and hope for the best.

The Cultural Risk Assessment Matrix

When an organization attempts to implement a change strategy that contradicts its organizational culture, it encounters significant resistance. Howard Schwartz and Stanley M. Davis highlight this issue and propose an approach to analyzing the alignment between culture and change plans. To do this, it is necessary to break down the strategy into tasks and activities and consider them from two perspectives:

The importance of each task for the success of the strategy.

The compatibility between the task and the culture of the part of the organization responsible for executing the planned activities.

There are four possible ways to resolve the conflict:

Ignore the organizational culture that hinders strategy implementation.

However, this approach is like trying to drive a car with the handbrake engaged. Sure, you might make some progress, but it'll be slow and painful.Acknowledge the existing difficulties created by the culture for strategy implementation and adjust the management system to align with the existing culture.

This involves identifying the following factors: the strategy itself, the desired state, cultural barriers, and possible alternative solutions. The key here is to recognize that your approach isn't a perfect match for the current environment and finding a way to adapt either the approach or the environment for a better fit.Attempt to change the organizational culture to enable the achievement of set goals.

This is the most challenging option but also a very common one. From this perspective, it requires patience, persistence, and careful navigation – remember how hard it is to turn the large ship around.Modify the strategy to align with the existing culture.

This point is about finding a middle ground, adapting your plans to work with the current culture rather than against it. Usually if you can't change the direction of the wind, you have to adjust your sails.

How to Align Culture with Change

Senge's concept of building shared vision is particularly relevant here. A shared vision isn't a top-down directive; it's a collective aspiration that inspires genuine commitment. When employees feel they are part of something bigger than themselves, they are more likely to embrace change. Practical steps can be:

Start by assessing your current culture. What are its strengths? Where does it clash with your strategic goals? Tools like surveys, focus groups, and interviews can help identify cultural barriers to change.

Culture isn't something you impose; it's something you co-create. Involve employees in defining the values and behaviors that will support the change.

Use storytelling, recognition programs, and leadership behavior to embed cultural changes. For example, celebrate employees who exemplify the new cultural values, turning them into role models for others.

So, as we wrap up this episode of Tech Trendsetters, let's circle back to where we began: the frustrating paradox of the Disablement Cycle. We've explored how this self-reinforcing pattern can trap even the most capable organizations. But here's the exciting part – understanding the Disablement Cycle is the first step toward creating its opposite: the Enablement Cycle, where streamlined processes, trust, and measured risk-taking create a new cycle of innovation and progress.

And yet, I feel like we've only scratched the surface. The complexities of organizational change, the nuances of human psychology, and the intricacies of building effective processes could fill volumes. There are countless other aspects we haven't touched on.

But that's what makes this journey so fascinating. Each organization's path from disablement to enablement is unique, shaped by its own culture, challenges, and circumstances.

Remember, you're not alone in this struggle. Every tech leader I've met has their own war stories about battling bureaucracy and pushing for positive change. The key is to stay persistent, be strategic, and never lose sight of the ultimate goal: creating an organization that enables rather than disable its people. Stay enabled and see you next time!

Explore more: