The Schwerpunkt of Planning: Why Focus Beats Force

Planning isn't bureaucratic overhead — it's psychological warfare. Explore how German military philosophy applies to modern management, self-education, and IT.

There’s a feeling every professional knows, though few speak of it openly – that quiet dread that visits at odd hours, sometimes at 2 AM when sleep refuses to come, sometimes in the middle of a meeting when someone mentions a technology you should’ve mastered years ago. The endless backlog of tasks. The skills you promised yourself you’d acquire. And beneath it all, the creeping suspicion that everyone else has figured out something you haven’t.

Most advice tells you to work harder. Push through. Hustle. Grind. I find this advice not just unhelpful but actively harmful, a kind of cruelty dressed up as motivation, because it assumes the problem is effort when the problem is almost never effort.

The real answer, if I were to identify one, comes from an unexpected place: 19th-century German military philosophy. It has nothing to do with working harder and everything to do with a question that sounds stupidly simple: where and when do you concentrate your effort?

Today, I want to talk about planning. No, not the bureaucratic variety that produces fancy Gantt charts destined to gather dust in hard-drives. I mean planning as a psychological weapon, a tool for transforming what feels like drowning into something closer to swimming. Planning as the mechanism by which overwhelmed people become, against all odds, people who cope.

This may be one of the most misunderstood concepts in the world: the people who are perceived as successful, who get a raise at work, who have everything, aren’t actually smarter than you.. They possess no secret talent, no genetic advantage. They’ve simply understood something that sounds obvious once you hear it, but somehow remains invisible until then.

What is that thing? That thing is planning!

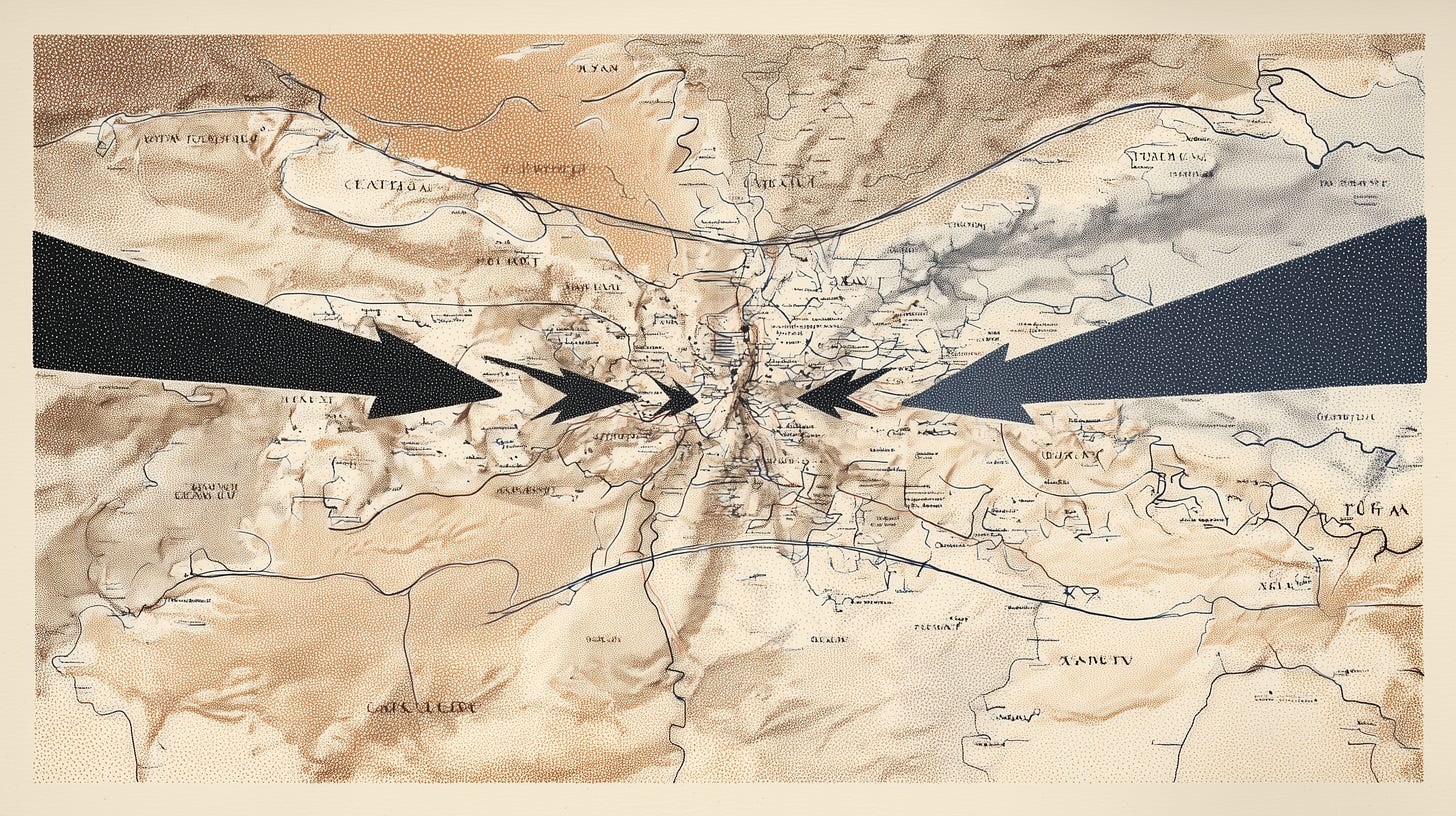

The Schwerpunktprinzip (Local Superiority Over Global Strength)

In German military doctrine, there exists a concept called the Schwerpunktprinzip – the principle of the decisive point, or main effort. It originates in the works of Carl von Clausewitz, Prussian general and 19th-century military theorist best known for “On War”, and later became a cornerstone of German operational thinking, one that military historians still study today.

If it were up to me, I would say this concept is not really known by most people outside specialist circles, but those who do know it often reduce it to something it isn’t – a doctrine of overwhelming force, of crushing superiority. The truth runs in precisely the opposite direction. The Schwerpunktprinzip was developed for situations in which Germany was not stronger.

German military thinking started from a realistic premise, one that applies far beyond warfare:

resources are always limited,

and the opponent is often superior in total strength.

Attempting to be strong across the entire front – spreading your forces, your attention, your energy in a thin, even layer – inevitably leads to dispersion, loss of initiative, and eventual exhaustion. A uniformly distributed effort favors the side with greater aggregate resources. If you’re not that side, uniform distribution is slow suicide.

The Schwerpunktprinzip proposes a different solution, one that feels almost like cheating once you grasp it: deliberately create overwhelming superiority at one carefully chosen point, at one carefully chosen time. On the scale of the entire front, you might be weaker or merely equal in strength. But at the decisive point (at the precise moment of engagement) superiority is consciously manufactured. Forces concentrate. Timing synchronizes. The direction of effort gets selected so that resistance is minimized and impact is maximized.

Is This a Military History Blog?

I know what you’re thinking: what am I reading right now? But this leads to what I consider one of the most liberating insights available to anyone who feels perpetually outmatched:

global inferiority does not prevent local dominance.

Success comes not from defeating the opponent everywhere, not from some fantasy of total mastery, but from breaking through at a single decisive point. After the breakthrough, the situation transforms. Forces advance. A new Schwerpunkt forms. The process repeats – step by step, point by point, until the overall objective is achieved. Victory through sequential local superiorities rather than impossible global ones.

Purposefulness of Local Superiority

But there’s another aspect of the Schwerpunktprinzip that deserves attention, one that separates strategic thinking from mere aggression: purposefulness. The decisive point is never chosen arbitrarily, never selected simply because it seems weak or convenient. Breakthroughs are executed where movement, supply, coordination, or progress is actually required – where success enables others to move forward, where a single advance unlocks multiple subsequent possibilities. Effort applies not where resistance merely exists, but where overcoming it produces systemic value.

Projected into professional, business and organizational contexts, this translates into something like.. wisdom?: the ability to recognize real needs rather than abstract ones, to focus resources where progress unblocks others, where momentum matters, where limited effort can shift the overall situation. It means asking not “what could I work on?” but “what, if accomplished, would make everything else easier or unnecessary?”

This broader principle (creating superiority at the right time and in the right place) extends far beyond military theory. It appears in nature, where predators succeed not through constant exertion but through explosive concentration at the moment of the hunt. It governs engineering, where structural integrity depends on reinforcing points of maximum stress rather than uniformly thickening every surface. It shapes sports and combat, where champions learn to read the moment when an opponent’s guard drops. It drives management and organizational psychology, programming and system design, learning and skill acquisition, even financial markets where timing determines everything.

Wherever resources are finite and resistance is uneven (which is to say, everywhere that matters) the Schwerpunktprinzip replaces brute force with focus, timing, and leverage.

So, did you wanted a magic pill for success? Here it is: from the entire front, identify a segment where you are able to concentrate your efforts and ensure superiority. That’s the whole secret (if it can be called a secret). Everything else is commentary.

Planning as Psychological Warfare (Against Yourself)

Now I want to bring this down from the abstract heights of military philosophy to the ground where we actually live and work. What does the Schwerpunktprinzip look like in the daily practice of management, of learning, of simply getting through the week without succumbing to that ambient dread I mentioned at the beginning?

It looks, more than anything else, like planning.

There is a classic IT book – “Planning Extreme Programming” by Kent Beck and Martin Fowler – in which Kent Beck explains something that changed how I think about this entire subject. He describes the enormous role that planning plays in relieving psychological pressure on management. The logic, once you see it, feels almost too simple to be true:

without a plan, a person cannot see whether their resources exceed the scope of work for the remaining period of time.

And this uncertainty, this inability to compare what you have against what you face, causes anxiety and tension of a particularly corrosive kind. It accumulates, it doesn’t discharge, sits in your chest during meetings and follows you home.

To relieve this tension, Kent Beck argues, resources need to be focused within each time interval in such a way that they exceed the scope – that is, you must regroup forces, concentrate them, create local superiority over your immediate tasks rather than spreading thin across everything that theoretically demands attention.

Without good planning, management usually ends up rushing, making decisions from a place of panic rather than clarity, and developers run headlong into a well-known humorous software engineering aphorism from the 1980s, often referred to as the 90/90 rule:

The first 90 percent of the code accounts for the first 90 percent of the development time. The remaining 10 percent of the code accounts for the other 90 percent of the development time.

And yes, this isn’t just an aphorism – it’s accurate. It’s a precise description of what happens when effort disperses rather than concentrates, when the end of a project arrives and everything that was deferred, avoided, or underestimated comes due at once. The 90/90 problem is the cost of operating without a Schwerpunkt, of imagining that uniform effort across time will produce uniform progress. It never does.

The Weight of Everything You Don’t Know

If planning matters in management, it matters even more (perhaps most of all) in learning. And become intensely personal.

One of the most important skills that helps relieve panic and depression in a developer, I’ve come to believe, is planning self-education. Without such planning, without some framework for distributing the acquisition of knowledge across time, the vast, knowledge-intensive horizon of required skills overwhelms the psyche. You look at everything you’re supposed to know (the languages, the frameworks, the architectural patterns, etc..) and the sheer volume of it intensifies what we’ve learned to call “impostor syndrome”, though that clinical term hardly captures the lived experience of feeling like a fraud who will be discovered any day now.

I’ve noticed something interesting, though, something that might point toward a way out. At school, they don’t evaluate the level of knowledge – they evaluate progress and performance. The teacher doesn’t expect a student to know calculus on the first day; they expect the student to keep up with the curriculum, to advance at the required pace. You don’t need to know everything. You just need to keep up with your own self-learning plan.

Without a plan, the entire weight of required knowledge concentrates in the present moment. It’s all here, now, pressing down, and it outweighs the brain’s resources by such a margin that anxiety becomes inevitable, even rational. The task, therefore, is to distribute the volume of knowledge being learned across time intervals where the brain’s resources will already exceed it.

Discipline as Liberation

Here’s the shift in thinking that actually produces results. Unlike the enormous volume of missing knowledge (which takes years to master), you can develop discipline right now. Today, this hour. Discipline concept is available immediately, and realizing this reduces your psychological dependence on what you don’t yet know.

The equation becomes simpler than you thought:

Either a person has discipline, and then they manage to do everything, or they don’t, and then they manage to do nothing.

But I should clarify what I mean by discipline, because the word carries connotations of white-knuckled willpower, of forcing yourself through pain. That’s not quite right. It’s really more about proper habits than sheer willpower, about constructing an environment and a routine in which the right actions become easier than the wrong ones.

Kent Beck, in the first edition of “Refactoring”, put it this way:

I’m not a great programmer; I’m just a good programmer with great habits.

This is a precise description of how expertise actually accumulates (consistency and sustainable pace).

To become a strong professional, it’s enough to master just five pages a day. Five pages. For example, Steve McConnell, best known as the author of Code Complete, did the math for us:

A little reading goes a long way toward professional advancement. If you read even one good programming book every two months, roughly 35 pages a week, you’ll soon have a firm grasp on the industry and distinguish yourself from nearly everyone around you.

Distinguish yourself from nearly everyone around you. Not through genius. Through five pages a day, sustained over time.

William James, the philosopher and psychologist, understood this truth in the late 19th century, well before anyone had heard of software development or impostor syndrome:

Let no youth have any anxiety about the upshot of his education, whatever the line of it may be. If he keep faithfully busy each hour of the working-day, he may safely leave the result to itself. He can with perfect certainty count on waking up some fine morning to find himself one of the competent ones of his generation.

Waking up some morning to find himself one of the competent ones of his generation. I love that phrase! It captures something essential, you become the thing you were trying to become.

Making the Invisible Visible

The best form of planning, I’ve found, is visualization – making the invisible architecture of your commitments visible to your eyes. You can draw tables, create timelines, use a Kanban board or Notion, use org-mode if you’re that kind of person, sketch on paper if digital tools feel like obstacles. The specific format matters less than the act of externalization (getting the huge mass of obligations out of your head and into a form you can see and manipulate).

When the plan is ready, or when you can look at it and confirm that yes, your resources exceed your scope within this interval, and this one, and this one – the only thing still needed is discipline. Simple discipline, which ensures you have a steady pace of progress.

The Principle of Local Superiority we discussed today, the Schwerpunktprinzip, doesn’t care about your industry. Like they say, it operates in boardrooms and bedrooms, in sprint planning and in Sunday evening dread. Wherever resources are finite and demands feel infinite (which to be fair, describes the most of adult life) the principle applies.

What I find most compelling about it is the quiet permission it grants. Permission to not be strong everywhere. Permission to let parts of the front remain unattended while you concentrate force elsewhere. Permission to be strategically weak so you can be tactically overwhelming.

The people who move through the world with real effectiveness have learned to let plates fall. The right plates, at the right time, so their hands are free to grip what matters.

Your plan is simply the document that records which plates you’ve chosen to catch this week, and which you’ve chosen to let shatter. Make it visible. Follow it with discipline. Trust the sequential nature of progress.

See you in the next episode! Until then – find your Schwerpunkt!