The Story Behind Story Points – Why They Might Expose Poor Engineering Culture

Why do story points make estimation more complex, not simpler? Learn the mathematical flaws, communication problems, and cultural issues that make story points a crutch for immature engineering teams.

Kent Beck created Story Points. Then he abandoned them. That should tell you everything you need to know, but somehow the industry missed the memo.

(If you’re lazy, feel free to stop here – you’ve already got the punchline – the rest of us are going deeper)

In the second edition of Extreme Programming Explained, Beck wrote:

The first edition of Extreme Programming Explained had a more abstract estimation model, in which stories cost one, two, or three "points". Larger stories had to be broken down before they could be planned. Once you started implementing stories, you quickly discovered how many points you typically accomplished in a week. I prefer to work with real time estimates now, making all communication as clear, direct, and transparent as possible.

Beck basically threw story points in the trash. Yet here we are, decades later, with teams religiously pointing stories in Fibonacci sequences. We adopted story points to make estimation easier, but we've made it more complex and less accurate.

Today I'm walking you through why story points expose engineering immaturity, and why teams that rely on them are usually avoiding harder conversations they should be having.

The Abstraction That Abstracts Nothing

There's an opinion that story points abstract team velocity.

Ron Jeffries himself, (the presumed creator of the term “Story Point”) disagrees with this. Here's what he says:

Story points as we originally defined them are in fact numbers. They are estimated days times a secret constant.

The logic that falls apart: until a team is assigned to a story, we can't plan because we're missing the key variable – the team's velocity. But as soon as the team is assigned (like at Cross-Team Refinement), the meaning of introducing an extra parasitic level of abstraction is lost.

Jeffries explains the original purpose: “In XP, stories were originally estimated in time: the time it would take to implement the story. We quickly went to what we called “Ideal Days”… We multiplied Ideal Days by a “load factor” to convert to actual implementation time. Load factor tended to be about three: three real days to get an Ideal Day's work done."

The problem was communication: "The result was that our stakeholders were often confused by how it could keep taking three days to get a day's work done... So, as I recall it, we started calling our “ideal days” just “points".

We're converting effort estimates into points, then converting points back into time for planning. In reality, team efficiency varies significantly depending on the nature of a particular task. Until we assign a team to a story, we cannot judge the team's efficiency.

And if teams can work at different speeds, then team efficiency is an attribute of the team itself, and this parameter could be made configurable in the project management system. A resource that isn't very good at some task might be pretty good at another.

The Mathematics Don't Add Up

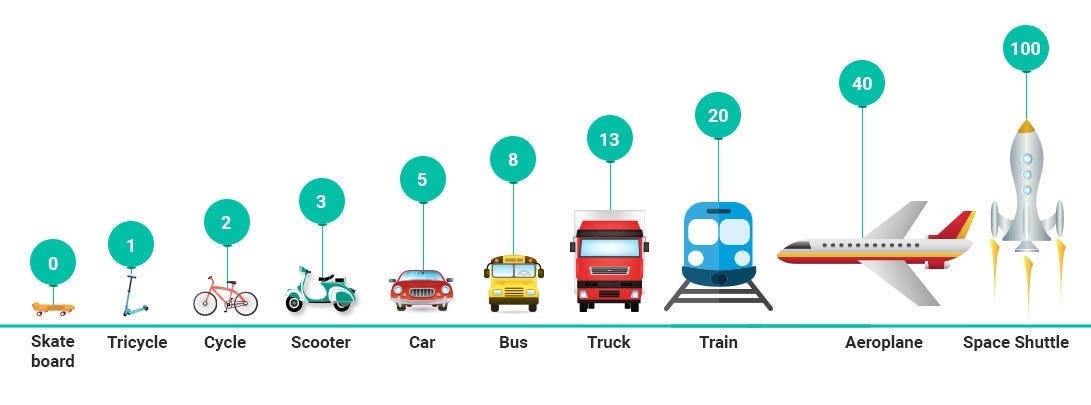

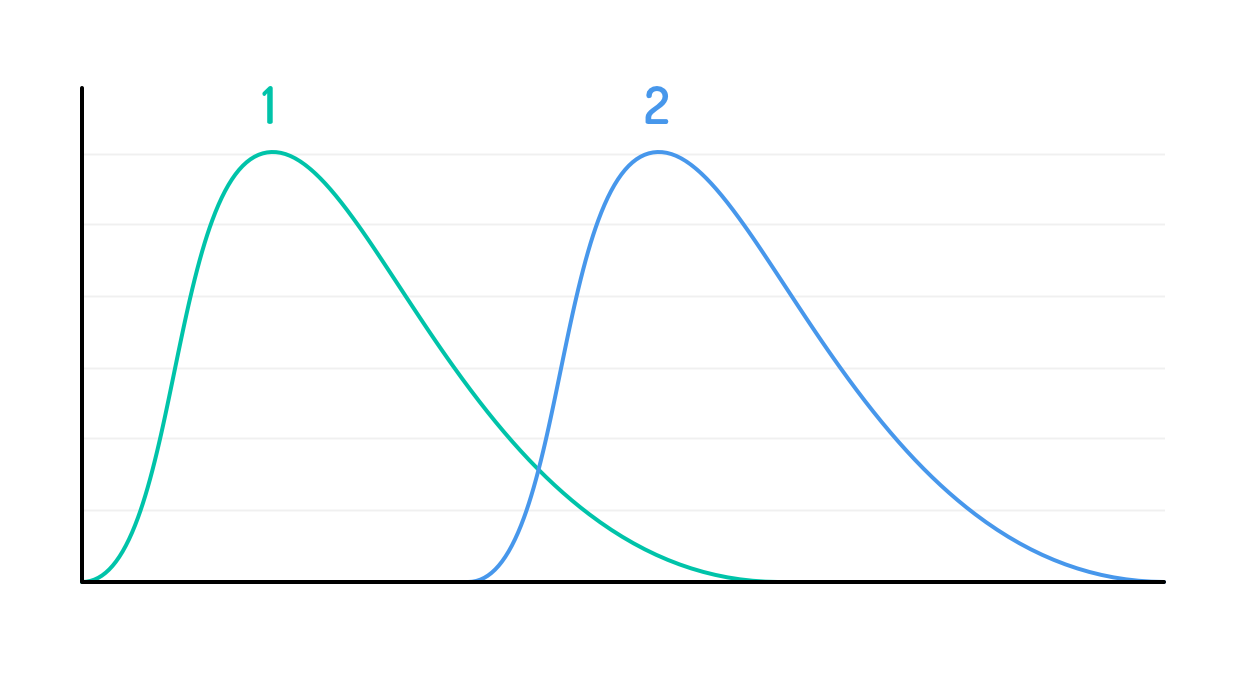

Most importantly, a story point combines both a probabilistic estimate and its standard deviation. That's why Fibonacci numbers are traditionally used – there's no point making the measurement scale more precise than the margin of error, which grows with task size.

But an estimate is a probability distribution, which cannot be expressed by a single value. Probabilistic estimates and standard deviations add up differently. There is no way to add up story points, which makes them useless for planning even if we know which specific team will implement the story.

Ron Jeffries is also very clear about this:

"No. However, the whole point of story points, like all other forms of story cost estimation, is to figure out how long things will take... If they can't be added, they are entirely without value."

We can (possibly) only sum them up over the short horizon of one or two sprints, where the inaccuracy of the summation is not critical. This way, story points are a more complicated and less accurate way of estimating for planning than, let’s say, PERT.

So is it really necessary to derive an abstraction from time, only to convert it back into time for planning, losing accuracy in the process?

When Story Points Reveal What's Really Wrong

Story points do have value, and that value lies in the reasons they were introduced. As Ron Jeffries said, they came up with story points because it was hard to explain why a task that was estimated at 2 ideal days ended up taking 5 calendar days. Story points were meant to fight the cognitive biases of development participants and to ease the tension between business and tech.

This is actually brilliant problem-solving, but let's call it what it is: a communication hack. When business stakeholders see "5 points" instead of "5 days," they're less likely to micromanage the timeline. When developers estimate in abstract units, they feel less pressure to defend their time estimates.

Again, this treats the symptoms while ignoring the disease. If your organization can't handle honest time estimates without creating toxic pressure, you have a culture problem, not an estimation problem. Story points become a way to avoid having difficult conversations about realistic timelines, technical debt, and uncertainty in software development.

The Effort Dodge

There is also an opinion that story points are not about time or effort, but about complexity.

Mike Cohn, one of the contributors to the Scrum method, argues against this view. He points out that teams often rebrand story points as "complexity points" because it sounds more sophisticated. But as Cohn simply said: "it's wrong." His argument is that story points should measure effort, which includes complexity as just one factor alongside volume of work, risk, and uncertainty.

I actually liked his example – imagine a team with a kid and a brain surgeon. Team has two tasks:

lick 1,000 stamps;

and perform a “simple” brain surgery.

The complexity levels couldn’t be more different, but if they take the same time, they get the same story points. Cohn's conclusion:

"story points are an estimate of the effort involved in doing something."

But here's what really bothers me about the effort vs complexity debate: it exposes teams that are uncomfortable with accountability. When you estimate effort, you're making a commitment about work. When you estimate complexity, you're making an academic assessment that feels safer.

The complexity argument is just another layer of abstraction piled on top of an already problematic abstraction. Teams that can't handle direct time estimates hide behind "effort." Teams that can't handle effort estimates hide behind "complexity." Each layer moves you further from useful planning information.

The Engineering Culture Litmus Test

As a way of solving communication problems, story points are still useful today in teams with a low level of engineering culture, because in that case the benefit outweighs the harm, since such teams are unlikely to be able to work competently with probabilistic distributions.

Teams with mature engineering practices can handle probabilistic estimates, honest uncertainty, and direct communication about timelines. They understand that estimation is about risk management, not precise prediction.

When you see teams clinging to story points, you’d usually spot other symptoms of engineering immaturity, such as:

they struggle with breaking down work appropriately;

they can't articulate technical risks clearly;

they haven't developed the vocabulary to discuss uncertainty with stakeholders;

they're afraid of being held accountable for time estimates, so they hide behind abstractions.

Nevertheless, Story Points have value for teams that aren't ready for more sophisticated approaches. If your team can't handle probabilistic thinking or honest timeline discussions, then story points might be better than nothing. But recognize them for what they are: a crutch, not a best practice.

The goal should be to outgrow them, not to perfect them. Even their creator moved on. Maybe it's time you did too!

See you next time!

🔎 Explore more: